The painting from the Temple of Lyon called Paradise is one of the most remarkable pieces in the Museum. A little decryption of a certain number of details sketched here by one of the main painters of the 16th century reformed.

The dog is a regular in Protestant engravings. Man’s best friend thus appears in the painting representing the Temple of Paradise exhibited at the MIR. It is believed that the dog symbolizes fidelity, the cardinal value of the Reformation, but its presence in the Temple could also indicate that the Church, under the Protestant regime, is now desecrated, this animal being often associated with impurity.

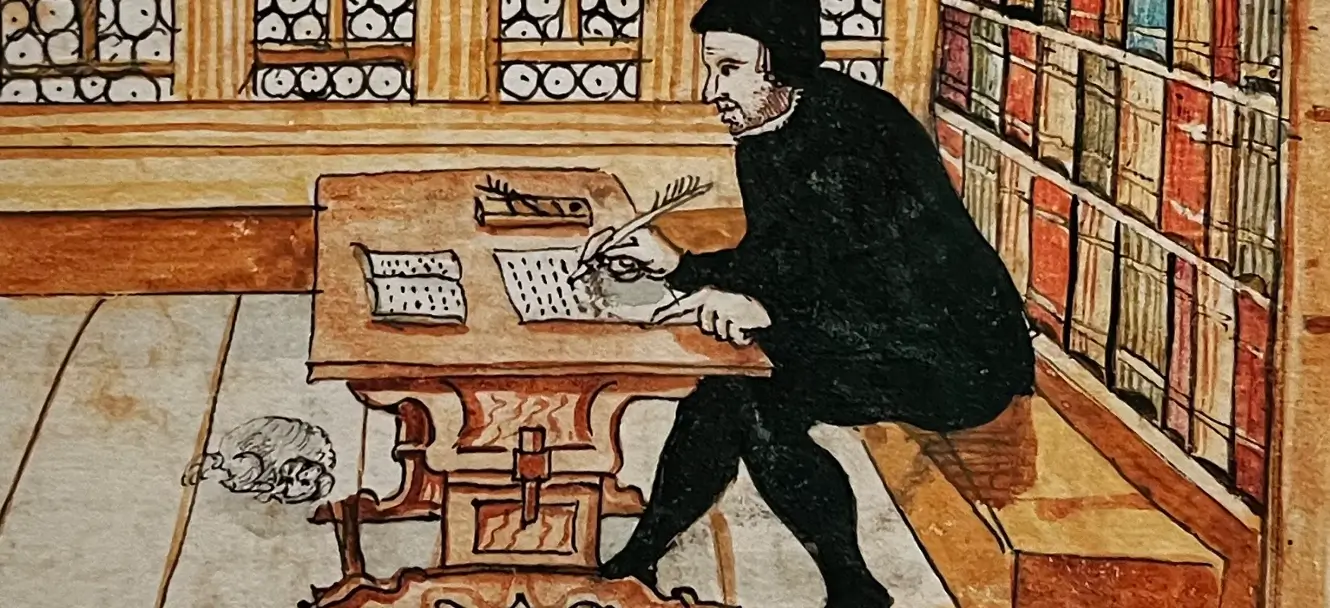

This painting was probably produced by Jean Perrissin, one of the authors of engravings also exhibited at the MIR in the Salle Barbier Mueller, taken from “Forty paintings or various stories touching the Wars, Massacres and Troubles that happened in France…”. The painting of the Temple of Paradise could have been executed some time after its destruction. Built in 1564 in Lyon, it was demolished three years later during the resumption of the religious wars in France.

This painting is one of the rare visual testimonies of the early days of the Reformation in France. It is the oldest representation of a Protestant temple. We observe a fundamental difference with Catholic buildings. The architecture is designed to make it easier to listen to the pastor who can be seen seated in his pulpit in the center of the image. A small hourglass on his right should warn him that he must soon finish his preaching. The faithful who surround him distribute themselves very freely throughout the building. We enter, we leave, we discuss, we discover each other, there are children, women, men carrying swords, others not, around fifty faithful in all, sketched in various attitudes highlighting a certain diversity of the ecclesial community.

Temple of Paradise

The painting from the Temple of Lyon called Paradise is one of the most remarkable pieces in the Museum.

We nevertheless perceive the terms of a social hierarchy since some parishioners can lean against a backrest while others must balance on uncomfortable wooden planks. As for the women, they are grouped in the same place, as well as a few children who can be seen with an open book on their knees, a catechism perhaps or a psalter.

It is not clear what ceremony takes place in the Temple. It could be a marriage, if we observe the two figures placed a little behind the pulpit, or it could be a baptism which is being prepared with the arrival on the left of a couple carrying a ewer (a sort of tin container filled with water) and a towel. But the child is not visible, or else it would be a question of baptizing the couple at the foot of the pulpit, a fragile hypothesis because Anabaptism under the Reformed regime was not current in Lyon at that time. .

We are also struck to observe both on the gallery and the backs of some benches the presence of fleur-de-lys which evoke royalty and power. Jean Perrissin, who was Protestant, probably wanted to explicitly point out that the Reformation had no political objective.

This painting representing the Temple of Paradise, hung on the walls of the MIR thanks to the generosity of the Library of Geneva which lends it to the Museum, underlines the dual vocation of the Reformers who were both translators and interpreters. It is rightly emphasized that one of the main achievements of the Reformation was to have democratized the reading of the Bible by favoring its translation into the vernacular languages of the time. But it was quickly observed on the side of the Reformers that these 1500 year old texts had to be interpreted and dialogue with each other, otherwise selective readings could cause a certain number of slippages or initiatives that were more revolutionary than reformed, such as the destruction of images in the name of the 2nd commandment or the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth from a reading without hindsight of the Sermon on the Mount.

Reformers as important as Luther and Calvin very quickly understood the dangers of reading without a certain number of guides and adaptations. We must understand the development of the University and of theology of which they were unwavering advocates, as remedies administered against an overly individualistic use of biblical reading.

From the top of his pulpit, but summoned by the hourglass to take into account the concentration capacities of an audience that we feel is slightly dissipated, the Reformed pastor explains the Bible and proclaims its truth based on the interpretations that he has developed for adapt it to the culture of its time. The painting of the Temple known as Paradise is a key to understanding the Reformed gesture of spreading biblical truths as widely as possible, even to the dogs « who eat the crumbs falling from their masters’ table. » (Matthew 15.27).

I make a bird for peace

On 21 September 2025, the International Museum of the Reformation joins the International Day of Pe...

RegistrationAll events

Google Analytics & Pixel Facebook

Google Analytics & Pixel Facebook